Introduction to containers

The objective of this series of blog post is to understand what is a container, how does it work and create a container to create and manage containers, from scratch in Rust. The implementation will be based on the amazing Linux containers in 500 lines of code tutorial, but rewritten in Rust.

First of all, to understand how we’re going to build our container, let’s figure out what is a container and why we need it, we’ll examine then few examples of containers commonly used.

About this tutorial

This tutorial can be read in 2 ways:

-

As a programming guide to get a good hand on Rust while building an interesting project

No prior experience needed to follow the guide, but keep the Book in a browser bookmark as you may need it to understand what is happening. -

As a detailed example of how Linux kernel features are used to achieve a great level of security and isolation in containers.

In this case, you can totally skip the coding part as the explanation will be mostly done before that.

Keep in mind that I am learning while creating this project, I may make mistakes and in case of doubts, please check the differents souces I give or the Internet to double check what I say.

It is mainly a way for me to learn about Linux security measures, virtualization features, how containerisation works, and the abilitiy to translate a program written with C paradygms with Rust, interacting with the Linux kernel. Fortunately for me, there’s a lot of documentation out there, videos, articles, etc …

I advice any reader to just go back and forth with the original tutorial to get precisions, an other explanation, and a bunch of links to the outer world (check the footnotes).

What is a container ?

Overview

A container is an isolated execution environment providing an abstraction between a software to be executed and the underlying operating system. It can be seen as a software virtualisation process.

So we basically tell a container “Hey, execute that thing inside a isolated box”, the manager create a box that will look like a system in which the container can execute (properly configured), and execute the software.

Usages

Containerisation is used by a lot of servers, as it allows great flexibility and reliability for DevOps engineers. Also if a software crashes, takes 100% of its resources available, or even gets compromised by a hacker, it wont hurt the whole system and all the other services who are running on it.

Note that servers use extensively virtual machines too.

Objectives

Containerisation solves issues met by programmers as the internet of microservices, the cloud, as well as the diversification of the computer forms (desktop, laptop, smartphone, smartwatch, smart<insert name here> …), running on more diverse operating systems.

Linux is everywhere and runs the digital world, but a Linux embedded on a car sensor isn’t the same as one on a desktop, a web server or a super computer.

Portability

Portability is the ability of a software to be executed on various execution environment without any compatibility issue, containers are one of the solutions to allow that kind of behaviour and is used to ship software without needing to modify the system to install it. So one can execute a software without installing it, and configure it to work on the system; it’ll just require to run a container (installed on the system), and let it handle the software.

From the Docker documentation website:

A container is a standard unit of software that packages up code and all its dependencies so the application runs quickly and reliably from one computing environment to another. A Docker container image is a lightweight, standalone, executable package of software that includes everything needed to run an application: code, runtime, system tools, system libraries and settings.

Okay, so it’s a way to make a software run without the compatibility hassle with the underlying execution environment. This is especially usefull to be able to develop a service and ship it to different servers, laptops or even embedded devices without all the problems it raises.

Isolation

But wait there’s more to it, containerized applications have an isolated execution environment from the underlying operating system, in the same philosophy as a virtual machine. The difference between a container and a virtual machine is explained on the Docker documentation also:

Containers and virtual machines have similar resource isolation and allocation benefits, but function differently because containers virtualize the operating system instead of hardware.

So we can run a software having administrator rights and performing any kind of operations without harming our system. Of course this is theorical and the real security will depend on a lot of factors, including the implementation, to avoid container evasion (the same way we would want to avoid virtual machine evasion), a great post about it is Understanding Docker container escapes.

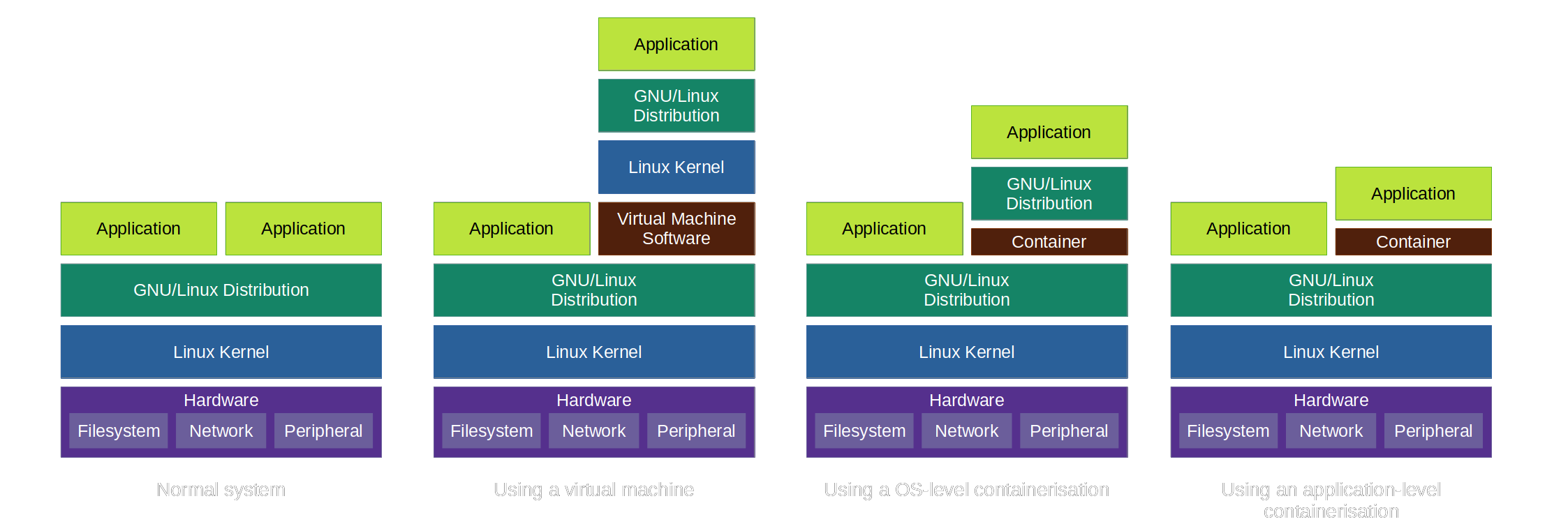

Naive representation of containerisation

Okay this representation is false for a lot of reasons, but intuitively there are different ways for a system to achieve the portability and isolation features. In reality, the CPU / SoC hardware have features to ease virtualization, but also the software stack under and inside the Linux kernel, but I won’t dive into these details here.

Okay this representation is false for a lot of reasons, but intuitively there are different ways for a system to achieve the portability and isolation features. In reality, the CPU / SoC hardware have features to ease virtualization, but also the software stack under and inside the Linux kernel, but I won’t dive into these details here.

However it is notable that a bunch of Linux libraries and kernel services allows to use the virtualization features, and we will use them extensively during the implementation.

Different containers use differents containerisation type, LXC for example is able to perform OS-level virtualization, whereas Docker will achieve an application-level virtualization.

Container = Isolated software

What we mean by “software isolation”, is the set of methods to allow a software to be executed inside the system, without allowing it to alter that system. So we want to create rules to forbid this software to access to files it’s not permitted to, to use system features it’s not allowed to, to modify the configuration of the system, to block or alter the performances, etc …

This can be done by a lot of different ways, but more generally it’s about implementing security measures around a software, strong enough to make this software totally blind about the underlying system.

So a container is just an application isolated from the system by a set of security measures.

Common containers

Of course, a lot of different solutions exist to create, execute and manage containers, but we’re going to inspect the 2 most famous one, Docker and LXC. A more complete list of containers can be found on Wikipedia.

Docker

The most used container, released as open-source in 2013, it is one of the fundamental tools used by DevOps nowadays when it comes to microservices and cloud computing.

One key feature it allows is to create containers in a form of a single image you can store and/or release, in DockerHub for example. Its usage and API are very high-level and it is fairly simple to add special configurations, access to a peripheral. Docker is a container focused on the application to run.

Visit the official website or its documentation to get more informations about it.

Linux Containers (LXC)

Once used as the backbone of Docker, LXC is the user interface for the containement features present in the Linux kernel. It uses kernel features to isolate and containerize an application to be run, and will attempt to create an execution environment as close as possible of a standard Linux distribution, without needing another Linux Kernel.

Visit the linuxcontainers.org website for more informations, including informations about the variants LXD, LXCFS and other related tools.

Next post in this serie: Starting the project